Don’t Die with the Music Still Inside You

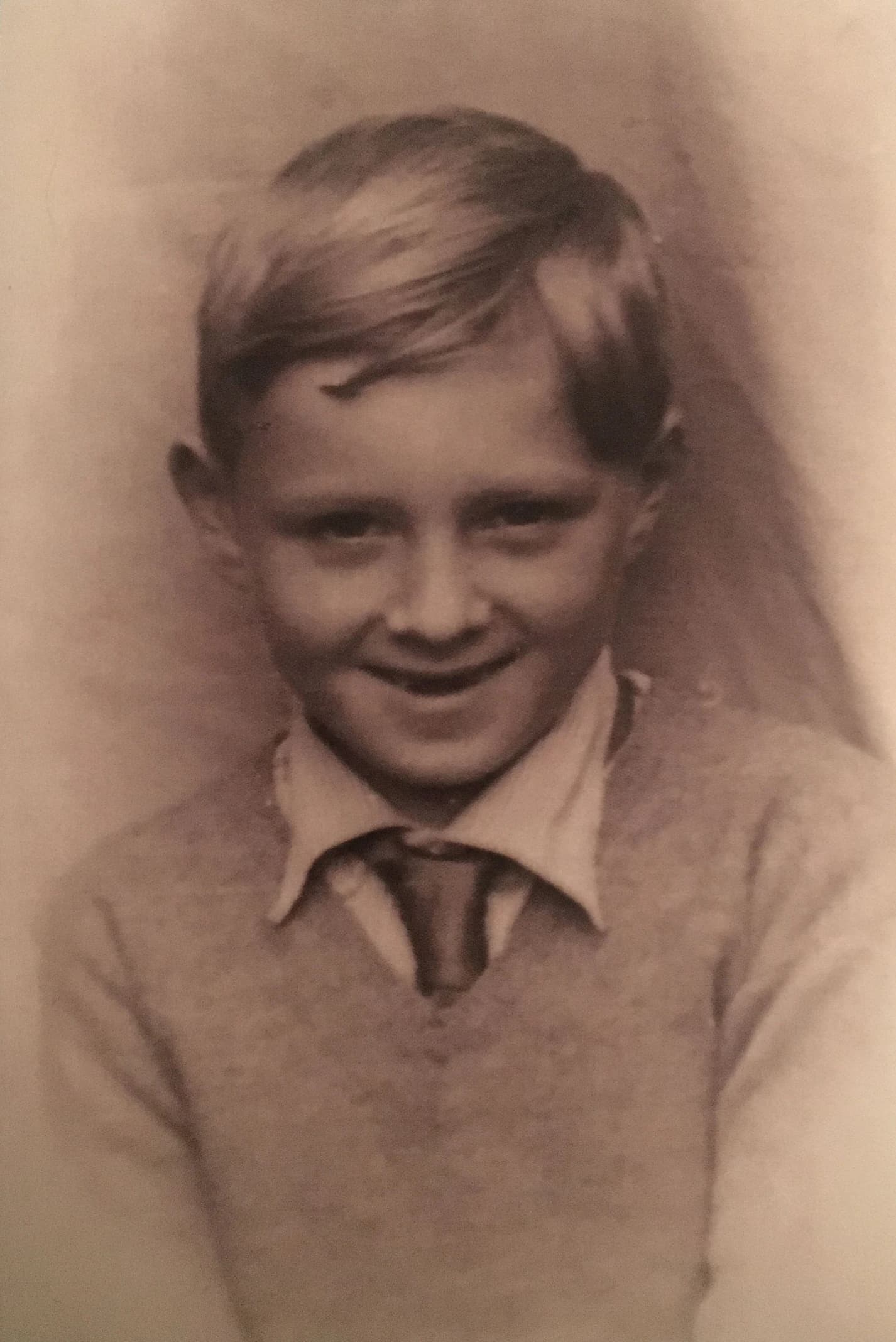

In Memory of my Late Dad

Two months ago, I flew to my native England to deal with the passing of my father.

For years, his now-widow had been by his side to help him in his decline through dementia, along with all kinds of physical issues from painful angina, through diabetes, bladder problems and multiple bouts of sepsis etc.

Living the other side of the world, I was only able to contribute in very minor ways to his care. At the very end of his life, as during multiple health emergencies over the last few years, my sister and half-sister stepped up to support him while he was in hospital.

So when he eventually passed, I had an opportunity to step up – to do something for him and something for his other family members who had been doing much more than I had for a long time.

My task was to handle the legalities and administration associated with his death, but also to clear out his things, which was a much larger job.

I was somewhat surprised by how many things he had kept. He was by no means a hoarder, but his garage was filled with boxes whose contents reflected chapters of his life and most notably, attachments to his parents, especially his mother, that had seemingly changed little even after their passing many years ago.

I spent days sifting through his possessions, putting many in the trash, helping sell a few, and taking the rest to local charity stores. It took about 30 trips; I had no car so was pushing boxes on a dolly.

In performing this task, I inevitably realized what billions of people have realized before - something one knows intellectually but doesn’t know experientially until one is physically and directly dealing with items that are of a person but no longer owned by the person. These are items that cease to be possessions not because of anything that has happened to them, but because of what has happened to their owner: upon death, one doesn’t only cease to own; one ceases to be able to own because one ceases to be anything on this earth at all.

It is a moment rarely and briefly encountered. The luckiest of us will encounter it only twice with the force that the loss of a parent gives it – once for Dad and once for Mom.

The strangeness of the experience perhaps arises from the fact that all man-made things are either owned or have just been made to be owned, or enjoyed, or used, so until you deal directly with your first death, every object you’ve ever seen or touched had a purpose. But an object left by a dead man is a kind of null object: the purpose for its existence - for its being wherever it is - passes with its owner.

Such a thing becomes in an instant stripped down to pure materiality - pure thing-ness.

Put more prosaically, in dealing with my dead Dad’s things, I got to experience stuff as absolutely nothing whatsoever but stuff.

Most of what we own is just a job for someone else to do when we can no longer own anything. The Swedish even have an approach to house-cleaning with that in mind; it's called "Swedish death cleaning," unsurprisingly enough.

It goes without saying that many of my father’s possessions – especially the most representational things, such as photographs - mean something to me because of what he and my family mean to me. But even those things that I kept for myself or other family members that Dad left behind were tinged with this new sense of being “mere stuff”.

When I, my siblings, and my Dad’s grandchildren have all passed in decades hence, not only will his cuff-links, for example, be just any old pair of cuff-links: those photographs will be just bits of paper. Even the ones of his grandfather (my great-grandfather) and his father (my grandfather) taken in Vienna just before they last saw each other as the former was bundled off by Nazis to Dachau in front of his son's eyes – even those will in a generation or two become nothing more than bits of paper.

Things that have so much meaning (concentration camp victims tended to want to keep their family photographs more than any other possessions) ultimately have none.

What I can’t quite get past is not that things like my dad’s photographs etc. will one day be thrown away because they mean nothing to anyone alive: it’s something a little more subtle and terrible than that: it’s that I can’t even imagine anything else more sensible to do with them than to throw them away. I hate that. It feels simply wrong. I hate the sense that the greatest meaning dissolves into none whatsoever. For a people-and-place sentimentalist such as myself, it is too big to process.

I’m not making a metaphysical point about the meaning of our existence or of the universe or what "meaning" might mean. It’s more of a gut response to the utter irresistibility of the transience of even those things that we who find ourselves in the universe experience as the most permanent things of all.

But it wasn’t even that, that got to me the most.

What really got to me was a new perception not of things – but of time.

And I don’t just mean that almost banal point that “we’re all going to die and my time is coming sooner rather than later,” although I certainly have felt that continuously and in spades since executing my Dad’s final wishes.

To explain this new “sensation” of time, I need to mention that thing that we often equate to time and that does in fact link time to stuff – money.

My Dad worried hugely about money at the end of his life. He had little of it and whereas his wife’s work income and his little pension were enough for them to live off month-to-month, the cost of emergencies was coming out of his rapidly depleting and minimal savings.

As it happened, Dad died, thankfully, with enough in the bank to pay for the funeral etc. and to make sure that his widow would be financially safe through her period of grief.

But as I was clearing out his things – all that stuff, almost none of which he had used or enjoyed for decades – I was less bothered about the fact that “you can’t take it with you”, than I was about the fact that the time a person spends earning the money to acquire all that stuff is not only, like the stuff, impossible to take with him: it’s time he didn't use to do absolutely anything in the entire world that would have brought joy.

What will determine what a person spends most of his time doing tomorrow (if tomorrow’s a weekday)? With at least 90% accuracy, the answer is whatever he was doing today.

Shouldn't that kind of passivity of mind scare us just a little bit?

We don’t often stop to wonder about the absurdity that so many people with the good fortune of living in a rich country with myriad possibilities and opportunities spend most of their waking lives unthinkingly doing the same thing tomorrow as they did today for the mere purpose of earning money that will either buy stuff that they cannot take with them or that will be left in a bank account that they also won't be taking with them.

It’s not that the time spent acquiring money was spent badly or for little: in a profound sense, it is spent for no purpose whatsoever unless the money earned is converted into positive experience.

Now, I realize, of course, that most of us need a financial cushion to feel comfortable and that is especially so at the end of our lives. (I certainly do.) But many of us middle-class types with the privileges of education and living in a stable and peaceful society work well beyond that point and we’re doing so in countries where systems like the NHS or Medicaid or similar will bear much of the expense that we will face for medical care at the end of our time as physical beings.

What is the point of spending one’s 30s, 40s or 50s - when one has the health, energy and wherewithal to do anything one would love to do - just to save more money for the end of life, when one will be unable to do any of those wonderful things that one chose to forego just to save the money?!

The madness of working tomorrow on whatever one did today without deciding tonight that you want to do that more than anything in the world is not so much that “you can’t take it with you” or even that “there are no pockets in shrouds”: it is that other old saw: “time is non-refundable”.

I lost another relative in the middle of the last decade, about whom I’ve written elsewhere. He was a very rich man who died with hundreds of millions in the bank. He left it to a charity that he had set up to plant the largest deciduous forest in England.

He is one of the few people that I know who lived a truly big life – big enough and creative enough that I couldn’t accuse him of not living deliberately, or of thoughtlessly working on a thing today simply because he worked on it yesterday. In fact, he was a serial and brilliant entrepreneur and died as Britain’s best selling poet (as well as one of its richest men)! For a large part of his life, he had planned to be buried in a glass pyramid with the epitaph, “Felix Dennis: everything, all the time.” I’ve never heard a better epitaph than that – or indeed of a better way of living life! And whereas for anyone else, such an epitaph would be utter immodesty, for him, it would have been (should he have ultimately chosen to use it) simply accurate.

Nevertheless, one night since my Dad's passing when I was pondering some of the above, I was looking online at some of my Uncle Felix's work and I came across this passage from one of his books (which I heartily recommend by the way):

If you are young and reading this then I ask you to remember just this: you are richer than anyone older than you, and far richer than those who are much older. What you choose to do with the time that stretches out before you is entirely a matter for you…. Money is never owned. It is only in your custody for a while. Time is always running on, and the young have more of it in their pocket than the richest man or woman alive. That is is not sentimentality speaking. That is sober fact.

And yet you wish to waste your youth in the getting of money? Really? Think hard, my young cub, think hard and think long before you embark on such a quest. The time spent attempting to acquire wealth will mount up and cannot be reclaimed, whether you succeed or whether you fail.”

Handling my father’s final affairs and reading my late uncle’s commentary again (I’d read it a decade ago but had entirely forgotten it) have changed me.

My Dad died with a few thousand pounds; my uncle with a few hundred million. But they both took the same amount with them – zero - and in so doing, they had both increased their balance sheets by the same amount from birth – also zero.

Monty Python famously quipped, “You've come from nothing; you're going back to nothing. What have you lost? Nothing.”

That line has been in my head a lot recently, but it’s morphed for me now to, “You've come from nothing; you're going back to nothing. What have you gained? Nothing.”

Except perhaps the experiences – and only the experiences - you had along the way.

In an obvious sense, you can’t take your experiences with you either (although I’m not entirely convinced of that), but at the moment of passing, unlike your stuff and your bank balance, your experiences won’t be worthless.

If you’ll excuse all the idioms, meditating on the above has brought home to me the utter seriousness of two more.

“Live each day of your life as your last,” and “Don’t die with the music still inside you”.

Doing what I did in October for my Dad has made that last one urgent. It’s already affecting my decisions.

I am a seeker, a thinker, and a writer. For those who care about these things, I am a text-book ENTP. I love to understand systematically what matters most, to formulate precisely original ideas about such big things as morality and knowledge in ways that could make a difference to those exposed to them, and then to express my ideas for just that purpose.

So for me, my “internal music” is intellectual – it’s ideas about fundamental matters, expressed in actionable ways.

It is unlikely that a large number of people will ever care about the ideas that I have been most excited to have.

I used to think that there’s little point expressing them (making my music) if no one reads them (hears it). Dealing with my Dad’s death has changed my mind.

I now think that there's no point living without making your music because to do so is to guarantee that no one will hear it and because - even more importantly - then you’d be living without making music when you have music that you would love to make, and there's simply nothing more meaningful to do than that.

Since my father passed on 6 October 2021, I’ve been working with more consistency than I can usually muster on a paper in moral philosophy that is too short to be a book (I’ve had one published) and too long to be an article (of which I've published hundreds); too short to be a PhD thesis but too long to be a Master’s thesis (I wrote one of those years ago); and too academic to be published on a non-academic platform, but not academic enough (I suspect) to be published on an academic one.

I have no idea when or how, therefore, I will ever get this latest piece of work seen (my music heard) in any place where it could have an impact and not be stolen.

It has taken hundreds of hours to write. The end is in sight but it is not finished yet. When it is, I shall be proud of it, but that doesn't mean anyone else will think it any good.

But it is music.

It is my music… which means that it is me.

It is music that no one else could ever make. And whether it is ever heard, I’m making it not because I was told to, or because that’s how I acquire stuff or money that I’ll likely leave behind - but because, although each life ends, life itself expands, and I get to choose which of those two different things - a life or life - most warrants my attention.

So do you.